On Tuesday, India’s Supreme Court refused to legalise same-sex marriage, disappointing millions of LGBTQ+ couples and activists. While these unions may still not have legal sanction in India, they were far from rare even centuries ago, experts say.

When author and activist Ruth Vanita attended and taught at the Delhi University – from the 1970s to 1996 – “same-sex love was almost never mentioned in the academy”.

Around the same time, she was active in the women’s movement, and found that a “similar silence prevailed then in feminist politics as well, both left-wing and right-wing”.

“Many of the leading activists in women’s groups were lesbians, but they never mentioned or discussed this in activist forums,” Prof Vanita, who now teaches at University of Montana, wrote in a 2004 essay.

Fourteen years later, in a historic decision, India’s Supreme Court ruled that gay sex was no longer a criminal offence, overturning a 2013 judgement that upheld a colonial-era law – known as section 377 – under which gay sex was categorised as an “unnatural offence”.

While some in India voiced concerns that the repeal of the colonial-era law was driving the country toward the adoption of Western ideals of liberalism, Prof Vanita’s argument was that history actually demonstrates the contrary.

Teaming up with historian Saleem Kidwai, Prof Vanita worked on Same-Sex Love in India: Readings from Literature and History, a collection of translations from texts in 15 Indian languages, complemented by essays that explained and analysed the material. “We conclusively demonstrated that same-sex love and romantic friendship flourished in ancient and medieval India in various forms, without any extended history of persecution,” writes Prof Vanita.

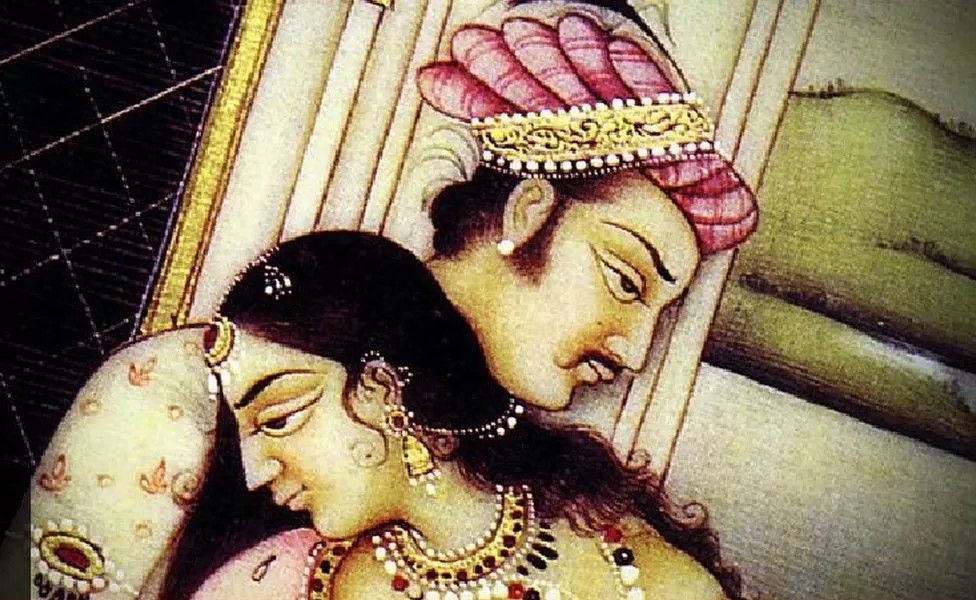

This sentiment was echoed by historian Rana Safvi when she told the BBC in 2018 that “love was celebrated in India in every form”. She said “whether ancient or medieval India, fluid sexuality was present in the society. One can see the depictions of homosexuality in the temples of Khajuraho and Mughal chronicles.”

On Tuesday, even the judges concurred. “Queerness is a natural phenomenon known to India since ancient times,” said Chief Justice DY Chandrachud. Justice SK Kaul added: “The significant aspect is that same-sex unions were recognised in antiquity, not simply as unions that facilitate sexual activity, but as relationships that foster love, emotional support and mutual care.”

In a paper on same-sex unions in India, particularly within Hindu culture, Prof Vanita contends that Indian perspectives on sex and love underwent a “radical” transformation during British rule in the country. “Indian nationalists imbibed Victorian ideals of heterosexual monogamy and disowned anything in indigenous traditions that seemed to flout those ideas,” she noted. Author Devdutt Patnaik says an “overview of temple imagery, sacred narratives and religious scriptures does suggest that homosexual activities – in some form – did exist in ancient India”.

The 4th Century Kamasutra, the world’s oldest textbook of erotic love, mentions that “two men friends who are well-wishers of each other and have complete trust in each other may mutually unite”. Prof Vanita writes she has found evidence in ancient texts of “parents deciding to accept their children’s cross-caste and cross-class marriages on the basis that the young people must have been spouses of the same caste and class in a former lifetime”. In the same way, these texts explain that same-sex attachments can last across lifetimes.

In 1988, newspapers reported on what is believed to be the earliest documented same-sex marriage in contemporary India: a small ceremony in Madhya Pradesh, where two policewomen, Leela Namdeo and Urmila Srivastava, solemnised their union.

The two were suspended from their jobs, although friends and family supported them. One of their neighbours, a married woman schoolteacher, told a journalist: “After all, what is a marriage? It is a wedding of two souls. Where in the scriptures is it said that it has to be between a man and a woman?”

Prof Vanita notes that since then, the media has covered a string of such weddings taking place in various parts of the country, involving predominantly young Hindu women. These brides hail mostly from lower-middle-class backgrounds in small towns, with limited proficiency in English. However, many possess some level of education and hold jobs, and notably, none of them have ties to women’s or LGBTQ+ advocacy movements. To be sure, these marriages carry no legal weight.

At the same time many same-sex couples in different parts of India were driven to taking their lives, similar to cross-sex couples – because “romantic love itself is seen to be opposed to social norms”.

Prof Vanita told me she remembers “the hundreds of young couples, mostly women, who committed joint suicide since at least the 1980s – this continues today – because they were not allowed to get married. And also a salute to the many other couples who have been getting married by Hindu rites since at least 1987, a time when same-sex marriage was not recognised anywhere in the world”. These “lower-income, non-English speaking couples are the true pioneers of marriage equality in India”.

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court said that legalising same-sex marriage was the job of the parliament. The court instead accepted the government’s offer to set up a panel to consider granting social and legal rights and benefits to same-sex couples.

“I am disappointed but not entirely surprised. Public opinion is veering in favour of marriage equality but is deeply divided, as are all political parties. India is, as far as I know, the only country in which the petitioners for marriage equality include people from the extreme right to the extreme left and everything in between,” Prof Vanita said.

Since 2001, 34 countries have legalised same-sex marriages. India will have to wait to join them: the success of this movement hinges on politicians hastening the shift in public opinion. But anti-discrimination rules would be a good start.