How many hours should a person work in a week?

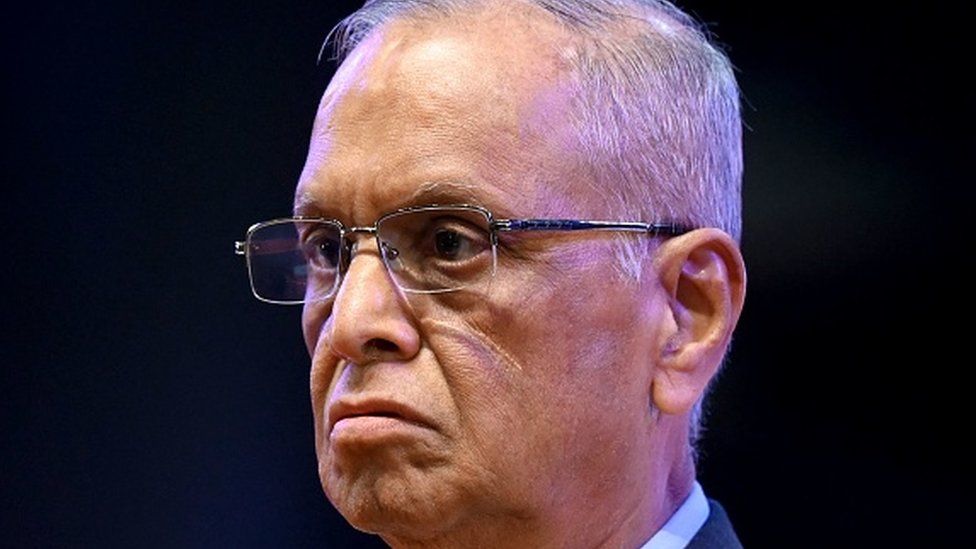

That’s the question being asked in India over the past few days after software billionaire NR Narayana Murthy – the father-in-law of UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak – said that young people should be ready to work 70 hours a week to help the country’s development.

“India’s work productivity is one of the lowest in the world,” he said on a podcast recently. “Unless we improve our work productivity… we will not be able to compete with those countries that have made tremendous progress.”

“So, therefore, my request is that our youngsters must say, ‘This is my country. I’d like to work 70 hours a week’,” he added.

After the comments went viral, Mr Murthy received both support and criticism as people on social media and the opinion pages of newspapers debated “toxic” work cultures, and what employers can expect from the people they hire.

Some of the criticism came from people who pointed out the starting salaries – typically on the low end – for engineers in Indian technology companies including Infosys, which Mr Murthy co-founded.

Others focused on the physical and mental health issues that could arise from working without a break.

“No time to socialise, no time to talk to family, no time to exercise, no time for recreation. Not to mention companies expect people to answer emails and calls after work hours also. Then wonder why young people are getting heart attacks?” Dr Deepak Krishnamurthy, a Bengaluru-based cardiologist, wrote on X (formerly Twitter).

And some pointed out that most women worked much more than 70 hours a week – at both the office and their homes.

The debate comes at a time when around the world, the Covid-19 pandemic has made people re-evaluate their relationship with work. Many felt that they were more productive when they worked from home while others advocated for a healthy work-life balance.

Experts say there are benefits to this, not just for employees.

“Companies that implement work-life balance policies benefit from increased retention of current employees, improved recruitment, lower rates of absenteeism and higher productivity,” said the International Labour Organization (ILO) in a report released last year, citing a study of 45 companies in the US.

Indians already work long hours – according to the ILO report, Indians worked an average of more than 2,000 hours every year before the pandemic, much higher than the US, Brazil and Germany.

“Boosting productivity isn’t just about working longer hours,” Indian entrepreneur and film producer Ronnie Screwvala wrote on X. “It’s about getting better at what you do – upskilling, having a positive work environment and fair pay for the work done. Quality of work done > clocking in more hours.”

The topic is a sensitive one in India – the country has strong labour laws but activists say officials need to do more to implement them strictly.

Earlier this year, protests from workers and opposition leaders forced the Tamil Nadu state government to withdraw a bill that would have allowed working time in factories to increase to 12 hours from eight.

Mr Murthy had earlier faced criticism in 2020, when he suggested that Indians work for a minimum of 64 hours a week for two to three years to compensate for the economic slowdown caused by the coronavirus lockdown.

Last year, another Indian CEO was criticised for suggesting that young people work 18 hours a day at the beginning of their careers.

But some business leaders in India agree with the advice.

CP Gurnani, CEO of IT company Tech Mahindra, said that Mr Murthy might have intended for the comment to be taken in a more holistic way.

“I believe when he talks of work, it’s not limited to the company. It extends to yourself and to your country. He hasn’t said work 70 hours for the company – work 40 hours for the company but work 30 hours for yourself. Invest the 10,000 hours that makes one a master in one’s subject. Burn the midnight oil and become an expert in your field,” he posted on X.

“A five-day week culture is not what a rapidly developing nation of our size needs,” said Sajjan Jindal, chairman of the JSW Group of companies.

While India debates longer working hours, some developed countries have been experimenting with four-day work weeks.

In 2022, Belgium changed laws to give workers the right to work four days a week without a salary reduction. The country’s prime minister said that the intention was to “create a more dynamic and productive economy”.

Last year, several companies in the UK participated in a six-month trial scheme, organised by 4 Day Week Global which campaigns for a shorter week – at the end of the trial, 56 of the 61 companies that took part said they would continue with the four-day week, at least for now, with 18 saying they would make it a permanent change.

A report assessing the scheme’s impact in the UK found that it had “extensive benefits”, particularly for employees’ well-being.

Its authors argued it could herald a shift in attitudes, so that a mid-week break or a three-day weekend would soon be seen as normal.

A similar experiment is now being held in Portugal.