As the celebrations for the BRI’s 10th anniversary kick off, attending countries would do well to ask whether their citizens have anything to gain from ‘win-win’ cooperation with China, Elaine Dezenski writes.

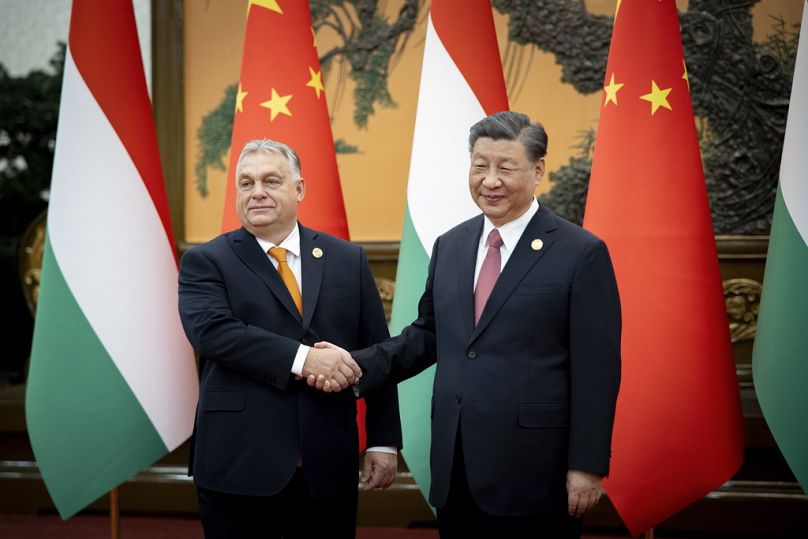

Xi Jinping’s Third Belt and Road Initiative Forum — and the 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) itself — launched on Tuesday, featuring a long guest list that includes Vladimir Putin and the Taliban.

In the decades since it was first proposed, the initiative and the world around it have changed profoundly. Optimism and ambition for the BRI have been replaced by broken promises, cracked dams, and wrecked state treasuries throughout the emerging economies and trading partners who took a chance on Xi’s signature infrastructure and investment program.

Introduced as a means to fund much-needed infrastructure and connectivity, the BRI has imposed a staggering bill on the countries that signed up for it.

Xi claimed at the First BRI Forum that the initiative would establish a “stable and sustainable financial safeguard system that keeps risks under control.” Instead, the opposite occurred.

Extreme public debt driving already poor nations into bankruptcy

Unlike Western lenders that often provide direct aid or subsidized loans, China lent $1 trillion (€948 billion) to cash-strapped nations at commercial rates.

Much more secret debt might be hidden from view, as a 2021 study suggested that as much as half of BRI loans are off the books and omitted from official statistics.

Instead of seeing clearly what is owed, we see the impact on nations, as Zambia and Sri Lanka are driven into bankruptcy and default.

With commodity-backed loans and secret contract terms that prioritised its debts over all other loans, Beijing is making sure it gets paid.

Argentina, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malaysia, Montenegro, Pakistan, and Tanzania are all dealing with extreme debt-to-GDP ratios that force crippling decisions in order to service the debt.

Since 2010, public debt has tripled in sub-Saharan Africa, driven largely by Chinese lending, and 60% of BRI countries are in debt distress — a 1,200% increase since 2010.

China may be losing some money too, as it has needed to fund $240 billion in bailouts in recent years — bailouts that extend that debt rather than forgiving it.

Nonetheless, with commodity-backed loans and secret contract terms that prioritised its debts over all other loans, Beijing is making sure it gets paid.

The unsustainable debt burden on countries is even more galling in light of reports of failing and wasteful infrastructure.

In Ecuador, a massive $2.6bn hydroelectric dam built at the foot of an active volcano has 17,000 cracks in its structure that force it to operate at limited power and risk failure or collapse. Dams in Uganda and Pakistan have structural cracks as well.

In Sri Lanka, elephants wander through a mostly empty international vanity airport built in the former President’s home district.

In Zambia, the massive Mongu-Kalabo highway linking western Zambia to Angola sees mostly foot and bicycle traffic.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), China didn’t build the bulk of the promised infrastructure at all — constructing less than $1bn of the agreed $3bn in infrastructure China offered in exchange for extracting critical minerals that have been valued at between $10bn and $17bn.

And through it all is Chinese-fuelled corruption. Chinese state-owned businesses paid bribes of $55m to President Joseph Kabila and his entourage in the DRC.

President Lenin Moreno and other officials in Ecuador received $76m in bribes related to the dam with thousands of cracks.

Chinese officials covered up and abetted the embezzlement of as much as $1bn by Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak.

China has touted the BRI as the shining example of “win-win cooperation” based upon “mutual understanding, mutual respect and mutual trust among different countries”.

Xi explained China’s approach under the BRI: “We have no intention to interfere in other countries’ internal affairs, export our own social system and model of development, or impose our own will on others.”

Xi’s conception of non-interference, however, clearly has some caveats, not to mention utility for Bejing.

BRI has proven useful as an avenue for Beijing’s global pressure campaign to push countries to support the isolation of Taiwan and in the introduction of domestic, anti-democratic surveillance and intelligence-gathering in recipient foreign countries — to say nothing of using military intimidation to enforce controversial maritime borders in the South China Sea and leveraging nominally civilian overseas BRI assets to support Beijing’s military.

The BRI has aided and abetted global attempts to undermine democracy, attacks on human rights and freedoms, widespread use of Chinese propaganda and misinformation, and intimidation of press and media in foreign countries.

Moreover, BRI has contributed to the distortion of multilateral institutions, interference in the electoral process of foreign democracies, and attempts to drive division between global democracies.

The BRI may not deliver high-quality infrastructure as promised, but there’s plenty of value for Beijing in disrupting democratic rules and norms.

As the celebrations for the BRI’s 10th anniversary kick off, Xi is sure to announce new slogans and evolving rationale in support of another dangerous decade of BRI engagement, but attending countries would do well to ask whether their citizens have anything to gain from “win-win” cooperation with China.

At the Second Belt and Road Forum, Xi announced a new tagline for the BRI: “Open, Green, and Clean”.

Perhaps at this Third Belt and Road Forum, the most honest tagline would be: “Recipients Beware — Serious Strings Attached”.