Governments around the world are “reaching beyond their borders” to attack their citizens abroad and silence dissent, an international rights group has said in a new report.

In a report released on Thursday, Human Rights Watch (HRW) identified a growing trend of “transnational repression”, in which countries target journalists, political opponents, human rights defenders, civil society activists and others across borders, causing a “chilling effect” on freedom of expression and association.

The 46-page report, entitled We Will Find You: A Global Look at How Governments Repress Nationals Abroad, details 75 cases of governments in more than two dozen countries – including Russia, Iran, China, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Ethiopia, Thailand, Saudi Arabia and Turkey – carrying out “human rights abuses … to silence or deter dissent” over the past 15 years.

Methods include killings as well as “abductions, unlawful removals, abuse of consular services, the targeting and collective punishment of relatives, and digital attacks”, spreading fear, not only among targets but also their friends and family, who may also become victims.

“Governments, the United Nations, and other international organisations should recognise transnational repression as a specific threat to human rights,” said Bruno Stagno, chief advocacy officer at the New York-based group.

Abuses

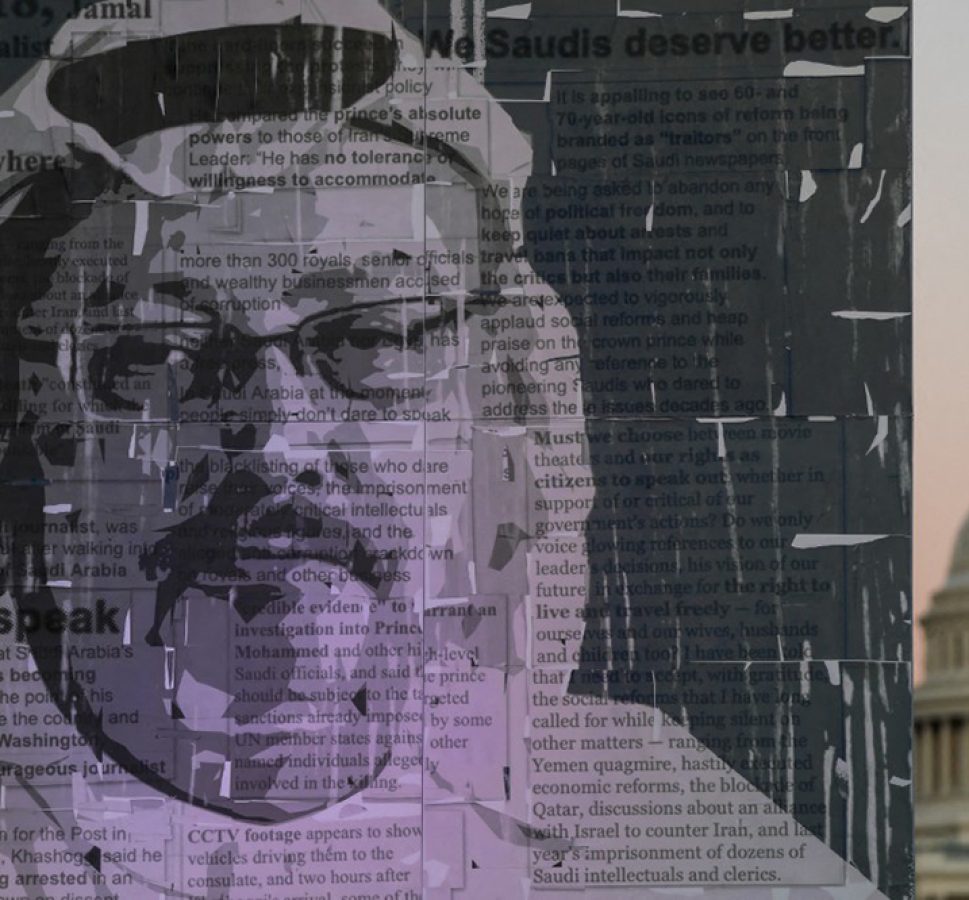

The examples mentioned in the HRW report include the 2018 murder of Saudi Arabian journalist and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi inside Riyadh’s consulate in Istanbul, Turkey.

In September 2021, Revocat Karemangingo, a former lieutenant in the Rwandan army who had refugee status in Mozambique, was targeted by the government in Kigali. His death served as a chilling warning to the refugee community, with reports of embassy staff threatening they would “end up dead like Karemangingo”.

Countries had also attacked family members to coerce dissidents into silence.

The report described how police in Chechnya abducted the mother of Ibragim Yangulbaev, who runs an antigovernment Telegram channel from abroad, and sentenced her to five and a half years in prison.

Removal, either through abduction or by using legal methods such as extradition or deportation, was also common.

HRW believes that Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) abducted Ruhallah Zam, an Iranian journalist exiled in France, while he was visiting Iraq. He was executed in 2020, following a trial the group described as “grossly unfair”.

Some governments have abused Interpol’s red notices, which trigger a global alert enabling law enforcement to arrest a person before a possible extradition.

In one case, Bahraini dissident Ahmed Jaafar Mohammed Ali fled to Serbia after Bahraini authorities tortured him, HRW said. But after Bahrain sentenced him to life in prison following “unfair” trials, then issued a red notice against him, he was arrested and unlawfully extradited in January 2022, said the report.

Some countries have taken steps to counter “transnational repression”, including Australia and the United States.

Australia passed legislation in 2018, responding to allegations that the Chinese government had intimidated members of the diaspora. Police launched a programme to advise Australians on what to do if they think foreign governments are targeting them.

The United States, which has trained staff at its Federal Bureau of Investigation to identify cases of “transnational repression”, has passed legislation to counter the use of Interpol for political aims.