Russia’s war in Ukraine and destabilising “hybrid warfare” actions on the eastern border put foreign and security policy at the top of the agenda for candidates and voters alike.

November, in Finnish, translates as ‘dead month’, and is nobody’s favourite time of year.

But the presidential election race is lighting up the winter murk of the Nordic nation, as Russia’s war in Ukraine and destabilising “hybrid warfare” actions on the eastern border put foreign and security policy at the top of the agenda for candidates and voters alike.

Finland’s EU Commissioner Jutta Urpilainen is the latest, and last, main candidate to join the slate for January’s vote. And she’s left it late.

The Social Democrat’s belated entry to the race betrays her prospects of winning – Urpilainen reportedly declared only now to allow herself the maximum time away from her EU job without actually losing it.

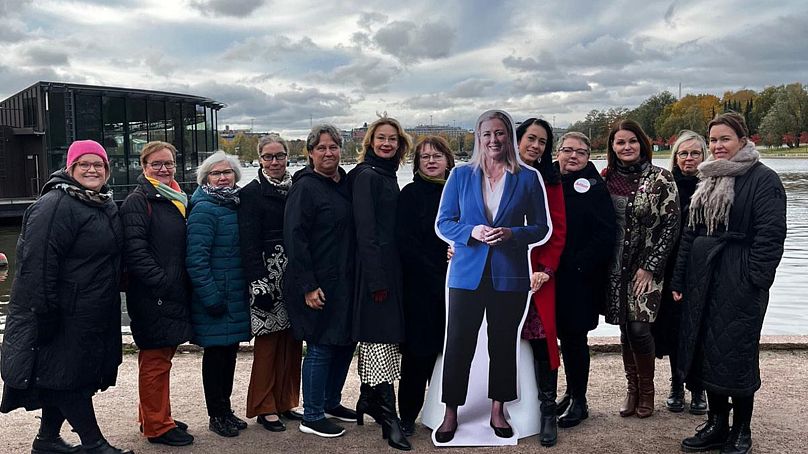

She won’t even start campaigning in earnest until December, which has meant that senior figures from her party have been left with the bizarre indignity of making public appearances holding a life-size cutout of the former finance minister just to try and keep her name in the public eye, while other candidates had launched their campaigns months before.

The powers of the Finnish president have shrunk over the last four decades but the officeholder still takes the lead on foreign policy outside of the EU and is commander-in-chief of the Finnish military. It’s one of the few presidential roles in Europe that is both directly elected by the people and wields executive powers.

The foreign and security policy campaign

Finland’s entry into NATO, and the geopolitical realities of being Russia’s neighbour during a time of war, have put a spotlight on this election like never before. It’s attracted some ‘big beast’ candidates with experience as prime minister, foreign ministers, party leaders, MEPs, and EU Commissioners on their resumes.

“We are now at the heart of Finnish security and foreign policy issues,” says Pekka Haavisto, a Green politician who was runner-up in the last two presidential elections and is a frontrunner this time round too. The former UN Special Representative and foreign minister would become Finland’s first Green, and first gay president if elected.

“People are asking about NATO, the future of Russia, the defence cooperation agreement with the US. And now in the last week there were many questions about the Middle East and how that influences world politics,” he tells Euronews.

“Even China and Taiwan issues come up regularly, people are following the news closely.”

Haavisto has woven together a broad coalition of well-known supporters from across Finland’s political spectrum – including from the parties of his rivals – as well as household names in Finnish culture and sport to back his third bid for the presidency.

“It was important to get those people with different political backgrounds behind my campaign, people have already made that choice based on personalities and not on traditional political party links. But for the first time in my campaign we have big names from the economic side too, and entrepreneurs,” he explains in an interview with Euronews as he heads to a campaign event in Eastern Finland.

“It is an interesting phenomenon, to show that I am not just a [left-wing] candidate.”

Former Prime Minister Alex Stubb is one of the other front-runners, with most polls showing the National Coalition Party candidate trailing Haavisto in the first round – where the outright winner would have to get more than 50% of the vote – and trailing in a possible second-round clash too.

With an estimated €1.5 million from supporters and the right-wing National Coalition Party at his disposal, Stubb is running the richest campaign this election cycle.

He benefits from having been out of Finnish domestic politics and above the fray in recent years, when he quit the country to work in Luxembourg and then Italy after leading his party to a fourth-place election defeat in 2015. A campaign to be ‘President of Europe’ also fell flat when he was defeated as the EPPs spitzenkandidat in a race that ultimately saw Ursula von der Leyen appointed to the role.

While Stubb, also a former foreign minister and MEP, is undoubtedly at home on the international stage, a perceived lack of interest in domestic issues has dogged his political career.

Being president would mean he’d have to spend significant amounts of time cutting ribbons, having tea with pensioners and visiting factories among the more routine and mundane tasks of the role, something party insiders concede he is ill-suited to.

Life on the campaign trail

The presidential election campaign season in Finland is long, with prospective candidates often jostling for attention already during the summer and then, once declared, subjected to an endless round of panel discussions, radio and TV interviews, shopping mall stump speeches, and shaking countless hands at market place meet-and-greets the length and breadth of the country.

“It’s a tough workload,” says Li Andersson, the Left Alliance candidate who is also the leader of her party.

“I have to build my campaign around my work in parliament because that’s what I’m elected to do. In January we have a break in the parliamentary session and I will be able to use those weeks to tour around the country, and I’ll be using weekends in December for tours,” she tells Euronews.

“I love meeting people, and you shouldn’t be in political affairs unless you love people. For me, that’s part of the job,” she adds.

“There is a strong sense of seriousness around the country when you give a speech and have a Q&A when I go to a marketplace or coffee shop or library,” says OIli Rehn, a former EU Commissioner on leave during the campaign from his job as Governor of the Bank of Finland.

“When you discuss foreign and security policy or what NATO membership implies, or Russian aggression or the president’s constitutional powers, there is a very strong and deep silence in the room and you can feel that people are very focused. There is a sense of seriousness in the campaign this time round,” the Centre Party candidate tells Euronews.

Despite the serious nature of the campaign overall, there’s also a lot of fluff in the hoops that Finland expects its presidential candidates to jump through to entertain voters and show some of their personality.

In the past, they’ve had to endure cooking segments on morning TV shows, while this time around candidates appeared on a prime-time Saturday variety show where a band played their favourite song and they had to tell the audience the story behind it – the sort of format a cynic would say is ripe for exploitation by any clever politician, who can concoct an emotional tale to warm even the iciest of Finnish voters’ hearts.

“These so-called lighter programmes have become part and parcel of all election campaigns at least in Finland. I take it as a fact rather than think whether I like it or not, I try to enjoy it as much as possible,” says Rehn, who recently stood outside a Helsinki library making lemonade with students to encourage them to become entrepreneurs.

“People are interested because they want to have the chance to glimpse and see the character and personality of the candidates.”

Smaller parties get equal billing during campaign

Traditionally in Finland, smaller parties have put forward a presidential candidate even if there’s no realistic chance of winning or reaching the second round. Individuals too can run for office if they first collect more than 20,000 signatures from voters.

This year there are candidates running from all the major political parties in parliament, including the Finns Party, Christian Democrats and Movement Now, but not the Swedish People’s Party. There are also individual declared fringe candidates who are unlikely to gather enough support to get on the ballot.

“There is a very competitive list of candidates who have ministerial jobs, and like myself who was head of a foreign policy think tank,” explains independent candidate Mika Aaltola, who did collect enough signatures and polled high during the spring and summer, but whose support has since cooled off.

“Clearly it is a crossroads for Finland, the citizens and political parties want to put forward candidates who have a lot of credible experience,” he adds. While Aaltola has the foreign policy chops as head of the Finnish Institute for International Affairs – he first broke through after a string of clear-headed fact-based media appearances when Russia invaded Ukraine – his lack of direct political experience has shown through as the race goes on.

He concedes that his campaign has only €25,000 in the bank, a fraction of most other candidates, and he relies heavily on a team of volunteers.

“I don’t have a PR agency or comms agency creating a campaign strategy. All that is missing,” he tells Euronews after a turbulent couple of weeks when he endured bad press following a series of gaffes which a more seasoned political operator would have known how to avoid in the first place.

The Left Alliance’s Li Andersson explains that it’s “important for democracy that you have a broad representative of candidates with views on foreign and security policy, and smaller parties can raise important questions for us and for a lot of voters too.”

Polling in the middle of the pack so far, Andersson is the youngest candidate in the field but has been party leader for the last eight years. As an MP she sat on the foreign affairs committee in parliament; she was minister of education in Sanna Marin’s government, and lead her party through two successful general election campaigns.

“This is the fora for talking about foreign and security policy, which is a hugely important part of the conversation in Finland,” she says.

The first round of the Finnish presidential election is held on 28 January. If no single candidate gets more than 50% of the votes, a second round featuring the top two candidates will be held on 11 February.