As the 44-year-old is sworn in after a crucial election, we chart the road to victory for Africa’s newest and youngest leader.

Dakar, Senegal – “Finally, we can breathe,” the cashier at the American Food Store supermarket in Dakar said while swiping a pot of Greek yoghurt through checkout.

It was three days after Senegal’s contested March 24 presidential election – the day provisional results were announced – and there was a sense that something had turned: a new vigour for democracy brought about by the election of opposition candidate Bassirou Diomaye Faye.

The 44-year-old was sworn in on Tuesday after a period of political turmoil and fears that outgoing President Macky Sall – who had already been in power for 12 years – would try to extend his mandate into a third term.

For months, the nation was on tenterhooks.

But after a whirlwind election cycle and last week’s landslide win for the young, anti-establishment candidate who was in prison just 20 days ago, there is now a palpable feeling among Senegalese that change has come.

‘Vote against the system’

On election day, voters began arriving at dawn, hours before polling stations opened.

Inside the playground of Nafissatou Niang Elementary School in Dakar that served as one of the polling stations, voters in flamboyant boubou robes, old suited men with newspapers in hand and young men in fake Balenciaga T-shirts, lined up, all standing in silence.

Among them was 37-year-old Julia Sagna, who said she was determined to use her vote to fight back.

Dressed in a grey power suit, she stood poised and a little nervous because she had never voted before. She said she never wanted to until she felt it really mattered. This time, she was sure: “The new, young voters would vote against the system,” she said.

Coming out of the polling station with a smile, she waved a pinky finger dipped in ink to mark that she had voted. “I feel lucky” to have participated, she said.

The delayed vote was supposed to have taken place in February. But days before campaigning was set to begin, Sall postponed the election for the first time in Senegal’s history, accusing the constitutional judges tasked with drawing up the list of candidates of corruption. Critics saw it as a last-ditch effort by Sall to cling to power.

But the Constitutional Council overruled the decision, ordering Sall to organise elections before the end of his mandate on April 2.

So on March 24, 66 percent of the seven million Senegalese eligible to vote went to the polls – a high turnout for a high-stakes election.

Arrested, then released

At the Medina polling station in downtown Dakar, large crowds gathered at the ballot boxes, some out of a desire for justice, others out for revenge.

Sall’s 12 years in office had been overshadowed by the political turmoil of the final few. In 2020, COVID-19 restrictions badly affected the informal economy and people’s livelihoods. The following year, the attempted arrest of opposition leader Ousmane Sonko ignited widespread anger towards the government, which was accused of ignoring the struggles of common people in favour of clamping down on political opponents.

Riots broke out, and the clashes turned deadly.

Scores of people were killed and hundreds injured by armed, masked men. The opposition and civil society saw them as goons hired by the ruling party, acting with impunity and paid to hurt people.

From March 2021 to February this year, thousands of people were arrested – among them Bassirou Diomaye Faye.

The former tax inspector had taken to Facebook to protest, writing a post in February 2023 that accused magistrates of being in the pocket of the state while overlooking actual crimes. The authorities deemed the post threatening to state security and, therefore, illegal.

That April, Faye was arrested and sent to prison, where he stayed for 11 months before being released just before last month’s vote.

At the time of his arrest, Faye had been working for Sonko, also a tax inspector. They were figureheads of the union of employees of the tax office upset with injustice and disparities at the tax department.

In 2014, Sonko, a firebrand with a soft tone and a sharp tongue, created the political party PASTEF (African Patriots of Senegal for Work, Ethics and Fraternity). The party attracted middle management civil servants who felt frustrated and powerless as they watched their superiors steal money and receive kickbacks with impunity.

Sonko came to fame by denouncing corruption in contracts for the lucrative oil and gas sector after natural gas reserves were discovered in 2014. In 2023, he was arrested on multiple charges, including provoking insurrection, conspiring with “terrorist groups”, endangering state security and immoral behaviour towards individuals younger than 21.

Shortly after, the government banned his party.

In 2018, Al Jazeera met Sonko in a small rented house overlooking a busy highway. During the interview, he lashed out at the government’s then-new law to control social media.

Little did he know then that the law passed in 2018 would be used five years later to arrest his deputy and the future president of Senegal, Faye.

On March 6, 18 days before the election, Sall passed an amnesty bill approved by parliament to release and pardon all those involved in crimes during the political violence that took place from 2021 to 2024.

Rights groups criticised the amnesty law, seeing it as a guise to protect the security forces and hired men involved in police brutality and the killing of protesters – crimes that will now no longer be investigated and, therefore, go unpunished.

But the amnesty also ensured the release of Sonko and Faye, who were freed less than two weeks before the election, bringing their presidential campaign to life.

The ruling party candidate, Amadou Ba, may have had the help of dozens of PR companies, but for many Senegalese, his messaging appeared tone deaf to the aspirations of the young majority, who desired change instead of more of the same.

Ba frustrated the media by arriving late to his own meetings or not showing up at all. Despite being the ruling party candidate, Sall also never appeared by his side.

‘Diomaye is Sonko’

Meanwhile, Faye and Sonko put on a show. They crisscrossed the nation, surrounded by bodyguards holding back frenzied crowds of young people wanting to get a glimpse of the men – as if the two were rock stars and not former tax inspectors.

The crowds sang the anthem to their campaign: “Sonko is Diomaye, and Diomaye is Sonko.”

Largely unknown to the public, Faye was until then riding the wave of Sonko’s popularity. But Faye stepped into the limelight.

Broom in hand, he promised “sweeping” change from a new currency and the renegotiating of oil and gas contracts to changing Senegal’s relationship with France and the French language. Under Sall, critics viewed Senegal’s government as a puppet to Western interests and one that put France’s interests above Senegal’s.

Faye promised he would put “Senegal first” and make the Senegalese his priority.

Overwhelmingly funded by the Senegalese diaspora from Europe and North America, Faye and Sonko ran an American-style campaign, campaigning as a duo “Diomaye Sonko” on a pan-African ticket. They filled up stadiums and lit up the sky with fireworks.

The show paid off. Two hours after the polling closed, a landslide victory appeared certain. One after the other, candidates conceded defeat and congratulated Faye.

By Friday, the official final results were confirmed. He had won 54 percent of the votes.

‘Sweeping’ victory

From political prisoner to president in fewer than 20 days, Faye is now Africa’s youngest leader at 44.

For his supporters, Faye was not the only winner. In the wake of the vote, people rushed to Sonko’s home. Under a flyover leading to Sonko’s house, where police had manhandled people trying to get to work in June, a victorious crowd gathered.

With horns blaring, young men on the rooftops of SUVs waved the green, red and yellow flag of Senegal. Some approached the area with their families and children. Supporters with brooms in hand swept the streets, a symbol of what they viewed as a sweeping victory.

But once the dust settles, people will want to know who is actually holding the broomstick.

When Sonko was barred from running in the election because of his criminal convictions, he chose Faye to stand as a candidate in his place. “A rational choice made not from the heart,” Sonko said in November at the time of his decision when Faye was also in jail.

Humble beginnings

Released on March 14 under Sall’s amnesty law, Faye will now settle into his presidential role. But his beginnings are far different from the elite he is replacing.

An hour-and-a-half drive from the capital is a long dirt road leading to Ndiaganiao, the village where Faye was born and raised.

It was here in 2022 that Senegal’s new president campaigned to become the village mayor but lost.

“Overcoming adversity and failure made him a success,” his father, Samba Faye, told Al Jazeera a day after the initial results were announced.

The elder Faye lives in a modest cement home in a sandy settlement. Blue plastic chairs were stacked in one corner, others strewn across the courtyard. Pots emptied of food lay around after the previous night’s victory celebration.

Not far from the home is a mosque, and nearby in the sand, the final resting place of Faye’s grandfather.

The family is recognised among the villagers, and the newly elected president is a respected figure.

Faye’s grandfather fought as part of the colonial French army against Nazi Germany in World War II. But after that, he brought the fight home and took on French colonial administrators over the construction of a district high school, a battle that proved more difficult than the trenches of war because the French colonists saw educated Africans as a threat to their rule.

His persistence landed him in jail, but the school was eventually built.

This is where the future president went to school, his father said. And during his time off, the young man would help his mother and sister plant cereal grains.

Samba Faye has been a lifelong member of Senegal’s Socialist Party. His son grew up with left-leaning ideals, his father said.

“It’s easy to be proud of your son now when he gets so much recognition, but there was a lot of pain, a lot of hard work, to get where he is,” Samba Faye said.

As Bassirou Diomaye Faye takes office at the presidential palace, in his shadow is his mentor Sonko. Tight friends, for now at least, but what role will Sonko play? Especially since Faye would likely have never won without him.

Some see uncertainty ahead. Others see hope for a new beginning. But what is clear is that there will be change.

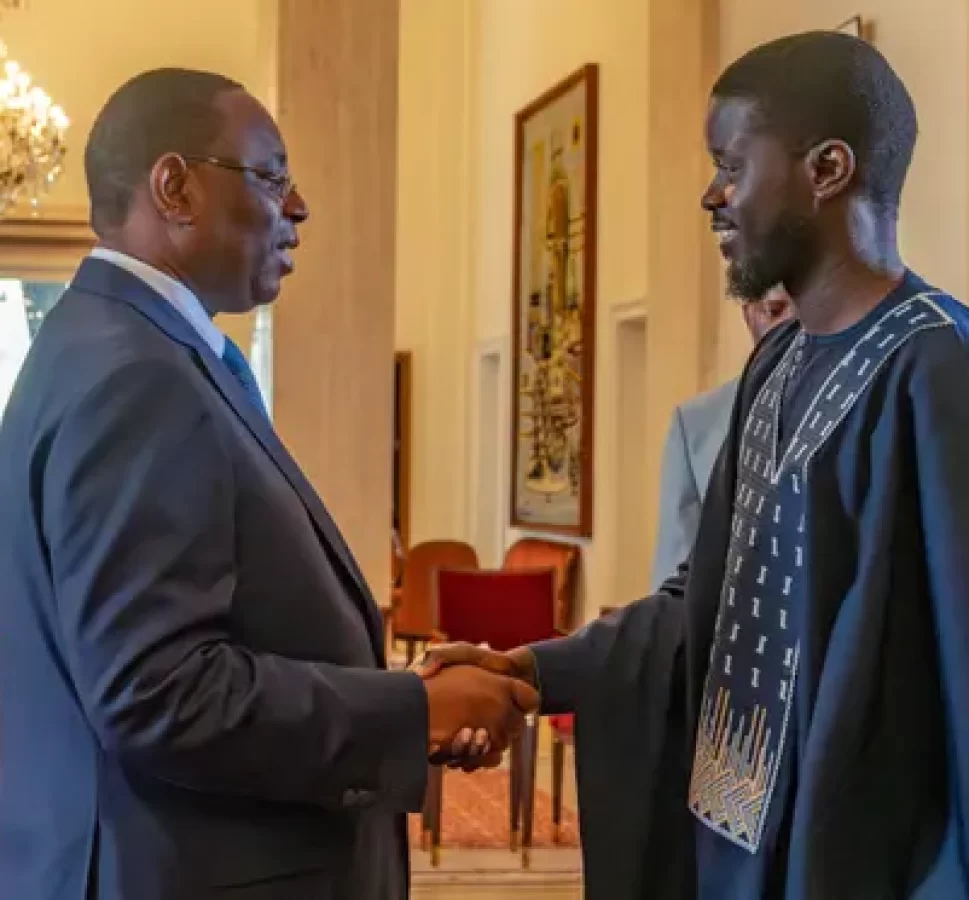

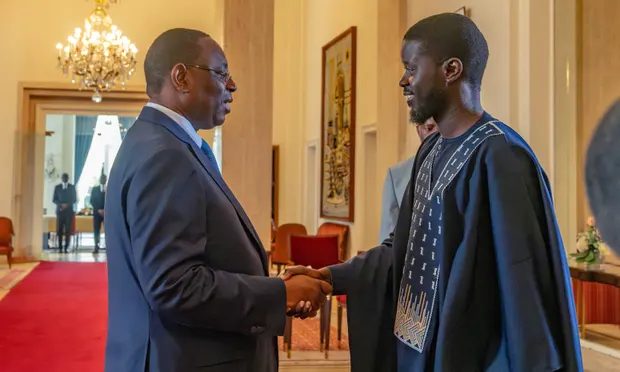

Before the handover of power, Sall met his successor. Sall, in a suit and tie, shook the hand of president-elect Faye and opposition leader Sonko, both dressed in traditional attire.

To some it may just be a symbol, but to the Senegalese who voted for Faye, it is a cataclysmic shift.