Efrat Eldan Schechter is a native of the Northern Galilee and never even considered moving anywhere else to bring up her family – that is until the events of 7 October.

When she heard and watched reports of what was happening in southern Israel that morning, as heavily armed Hamas gunmen streamed out of Gaza, she was immediately taken back to stories from the “Yom Kippur” or 1973 Middle East war, when Israel was attacked simultaneously on two fronts.

“I was terrified. Everyone was sleeping in and I thought it’s going to be ’73 all over again and Hezbollah is coming for us too,” says Efrat, as our interview in her front garden is punctuated by the regular loud thud of outgoing Israeli artillery fire.

“Immediately, I woke everyone up and very quickly got everything together and drove to a relative’s house in the centre of Israel.”

After a month the family returned to their house near Kiryat Shmona, frustrated because they’re still living on the edge of a war zone – a “buffer zone” as Efrat calls it – well within range of Hezbollah rockets being fired from southern Lebanon.

“What we fear most is that nothing will be done because Hezbollah are just waiting there on the border to come in and invade Israel,” says the mother-of-three. “I cannot sleep in peace. I want my government to make sure that we have real security here. If it is necessary, they should act and destroy Hezbollah infrastructure in Lebanon.”

Ever since violence here erupted on 8 October, when Hezbollah fired rockets and artillery “in solidarity” with the Palestinians, and Israel fired back, clashes in the north are generally confined to a three- or four-mile-wide (5-6km) strip along the entire border.

But they are intense and deadly – nine soldiers and four civilians have been killed in Israel, officials say, while authorities in Lebanon have reported that 123 people have been killed, including at least 21 civilians.

The frontier communities of northern Israel are today like ghost towns. More than 80,000 residents have been evacuated to centres further south, but Nissan Zeevi is one of the few who has stayed. The businessman, and civil defence member, shows me around his kibbutz – Kfar Giladi, just north of Kiryat Shmona. The scenery is beguiling as you look out over the lush, green Hula valley and Mount Hermon in the distance, but this border has always been volatile.

Like Efrat, Nissan does not believe most people can return to their homes and businesses until there is a guarantee of a lasting peace. He is particularly frustrated that UN Security Council resolution 1701, which helped end the 2006 Lebanon war between Israel and Hezbollah has not been fully implemented.

Crucially, says Nissan, 1701 calls for the demilitarisation of armed groups (specifically Hezbollah) in southern Lebanon. And that, clearly, has not been achieved.

Nissan is part of Lobby 1701, which has called for the implementation of the resolution “whether through diplomatic means or through a military action by Israel”.

“What we are demanding from our government is to take care of Hezbollah, to demolish the threat coming from those areas of southern Lebanon,” he tells me, as he points out the many Lebanese villages he can see from his own home and from where, he says, much of the incoming fire emanates.

When I ask him if he would support even more action by the Israeli government in southern Lebanon, Nissan says: “Absolutely! It’s not only me. A big proportion of the population of Israel is demanding the same.” “If we don’t do this, we will end up with another 7 October,” he adds.

Last month, I travelled to those very same frontier villages in southern Lebanon. They’re being hit daily by strikes because Israel says Hezbollah is hiding in communities to launch rockets and sophisticated weapons. Just as on the Israeli side, tens of thousands of people have left these areas too, and many have been killed. There’s loss on both sides of the border.

The possibility that this “contained” border conflict will escalate into a full-scale war came even closer on Monday with the apparent assassination of a senior Hezbollah commander, Wissam Tawil, when his car was hit in an air strike in Khirbet Selim. Last week, it is widely believed that Israel was also responsible for a drone strike in a Hezbollah stronghold in the Lebanese capital, Beirut, that killed Hamas’s deputy leader, Saleh al-Arouri.

None of this is good news for those trying to make a living near the front line.

Farmer Ofer “Poshko” Moskovitz of Kibbutz Misgav Am can’t bring in the kibbutz’s valuable avocado crop because the Israeli army says it’s too dangerous for him to spend time in his orchards, which are right up against the Lebanese border, north-west of Kiryat Shmona.

But, unlike many I spoke to in the north, this phlegmatic and jovial farmer does think a wider war can be averted.

“I’m not worried, because Israel is a strong country,” says Ofer as we wade our way through hundreds upon hundreds of almost ripe, green avocados strewn across the ground. He continues: “Nobody is looking for war here. We prefer to do it in a diplomatic way and they are looking for a solution – both the army and diplomatic efforts together.”

Ofer’s cautious positivity is in short supply in these parts.

Sarit Zahavi, who also lives close to the border, is the founder of the Alma Research Institute in northern Israel and spends much of her time analysing political developments among Israel’s regional neighbours.

“We are facing a very dangerous situation, in the sense that if there is to be a diplomatic arrangement, it would mean a ceasefire. And everybody will think that is good news,” she tells me.

“But, for me, if there will be a ceasefire, nobody will enforce the arrangement. Then Hezbollah will continue to grow, and will continue to develop its capabilities to invade Israel.”

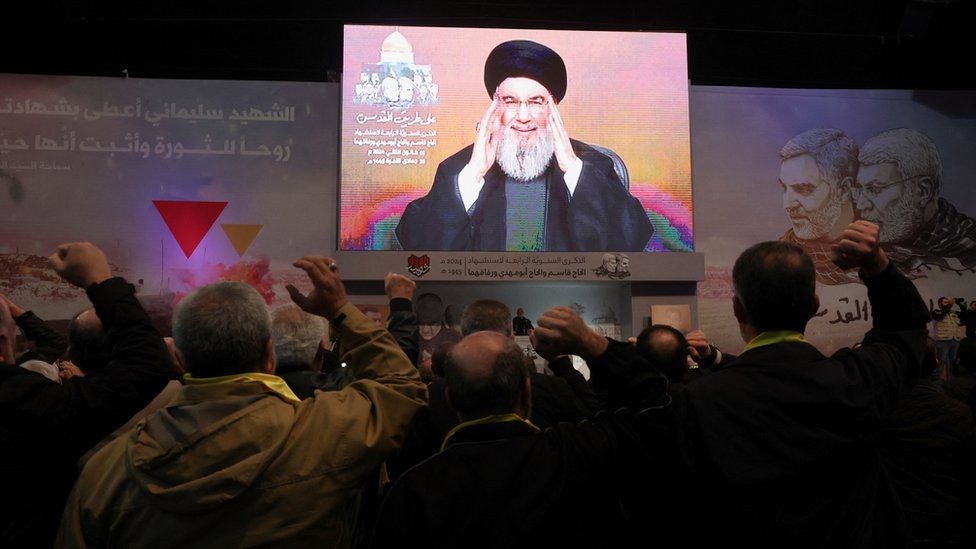

Fewer people, at least in northern Israel, seem to be confident that diplomacy can now avert a wider war. Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, has already vowed to retaliate for Israel’s actions and, Israel too, seems to be preparing for the possibility of an escalation.

On Monday, Israel carried out some of the heaviest bombing so far along its northern border just as the US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken arrived in Tel Aviv.

With the devastating war in Gaza and the latest developments in the north, the challenge for Secretary Blinken seems almost impossible.