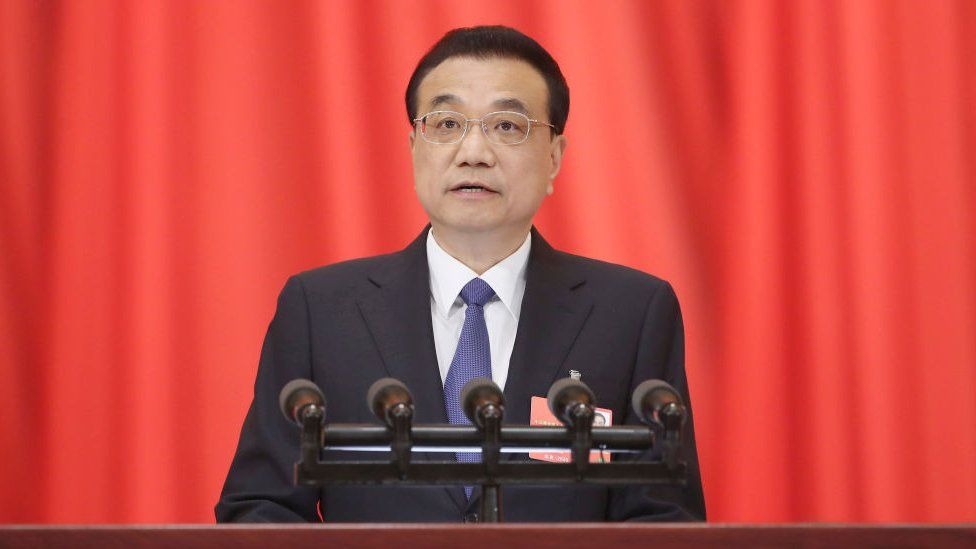

Former Chinese premier Li Keqiang has died of a heart attack aged 68.

State media said he died at 10 minutes past midnight on Friday despite “all-out” efforts to revive him.

Li was once tipped to be the country’s future leader but was overtaken by President Xi Jinping.

A trained economist, he held the second highest-ranked position in China, though in recent years, he was widely isolated amongst China’s top leadership.

He was the only incumbent top official who didn’t belong to Mr Xi’s loyalists group.

“Li’s death means the loss of a prominent moderating voice within the senior levels of the Chinese Communist Party, with no one apparently being able to take over the mantle,” Ian Chong, non resident scholar at the Carnegie China think tank told the BBC.

“This probably means even less restraint on Mr Xi’s exercise of power and authority.”

Li, who had stepped down as premier in March this year, suffered a sudden heart attack on Thursday and died early on Friday while he was in Shanghai.

His death is being widely mourned on Chinese social media, with many expressing shock and grief – though comments on many posts appear to have been restricted.

“This is too sudden, he was so young,” said one user on Chinese social media site Weibo. Another said his death was like losing “a pillar of our home”.

But his death has appeared to have been largely downplayed on state media outlets. No official language providing the party’s evaluation of Li’s career was provided in a terse initial statement by state news outlet Xinhua – no official obituary has yet been published.

Deaths of former Chinese leaders have triggered protests in the past. An outpouring of mourning during Jiang Zemin’s death last year was seen as a subtle criticism of President Xi.

Li was known as one of the smartest political figures of his generation. He was accepted into the prestigious Peking University Law School soon after the universities were reopened following Mao’s Cultural Revolution during which millions of people are believed to have died.

He is best known outside of China for the Li Keqiang index, a term coined by The Economist as an informal measurement of China’s economic progress.

The man who ‘told it as it is’

Li came from a modest family and was the son of a local official. He was born in July 1955 in Dingyuan County in eastern China’s Anhui province.

He rose among the ranks, becoming the youngest provincial governor in China and later earning a spot in the top echelon of the party’s central leadership, the Politburo Standing Committee.

At one point there was speculation that he would be groomed to succeed Mr Xi’s predecessor Hu Jintao.

He was widely considered to be Mr Hu’s protégé and was the last appointee of the Hu administration to remain on the Politburo Standing Committee before he stepped down in March this year. The Hu years were seen as a time of opening up to the outside world and increased tolerance of new ideas.

Li was known for being pragmatic in economic policies, with a focus on reducing the wealth gap and providing affordable housing.

“He was a very enthusiastic open man who really strove to get China ahead and facilitated open dialogue with people from all walks of life,” Bert Hofman, a professor at the National University of Singapore told the BBC’s Newsday programme.

Li will be remembered for being “open and reformist in his economic orientation”, said Dr Chong. “[He was] more of a technocrat than an ideologue or loyalist.”

Li pushed for policies to encourage entrepreneurship and technology innovation, especially among young people.

In a Party dominated by engineers, he was an economist who become known for “telling it like it is” – publicly acknowledging China’s economic problems as a means of finding solutions.

His economic policy of structural reform and debt reduction, termed “Likonomics”, aimed to reduce China’s dependency on debt-fuelled growth and steer the economy towards self-sustainability.

But by 2016, articles in the party’s mouthpiece People’s Daily had dropped “Likonomics” in favour of Mr Xi’s economic thoughts, which emphasised micro-economic reforms and advocated supply-side changes.

Hofman added that Li led China’s major campaign against air pollution during his time as premier, famously “declaring war” against pollution in 2014 and acknowledging at the highest level that it was a crisis for the country – leading to a significant reduction in pollution and associated health risks.

Li’s end of his time in office was mired in China’s zero-Covid crisis.

During the worst of it, he warned that the economy was under massive pressure and called on officials to be mindful of not letting restrictions smash growth. He even appeared unmasked in public before China lifted its zero-Covid policy.

But when cadres had to choose between his order to protect the economy and Mr Xi’s to maintain zero-Covid with extreme discipline, it was no contest – with China doubling down on restrictions.

Zero-Covid hit China’s economy hard, strangling supply chains and shuttering businesses, from economic hub Shanghai to rural towns.