The six-year inquiry condemns ‘decades of failure’ by governments, incompetence, dishonesty and greed.

Incompetence, dishonesty and greed were behind the 72 “avoidable” deaths in the Grenfell Tower fire in London, a report into the 2017 tragedy has concluded.

Delivered on Wednesday following a six-year inquiry, the final report stated that decades of failure by United Kingdom governments, indifference to safety by authorities, dishonest and incompetent manufacturers and installers of building materials, and a lack of strategy by firefighters were the main contributors to the shocking death toll.

Those in the 24-storey block were “badly failed” over many years, said the inquiry chairman, Martin Moore-Bick, speaking at a news conference on Wednesday. “The simple truth is that the deaths that occurred were all avoidable.”

He added that the two-phase inquiry, which has convened more than 300 public hearings and examined about 1,600 witness statements, took longer than hoped due to its broad scope and because “many more matters of concern” had been discovered than originally expected.

‘Incompetence, dishonesty and greed’

The long-awaited report said the elements identified contributed to varying degrees to the rapid spread of the blaze and failure to rescue residents. This was largely due to incompetence, the chairman said, but in some cases “dishonesty and greed”.

The first phase of the inquiry had found that the fire had been fuelled by the cladding used on the building, which was made of aluminium composite material (ACM), a mixture of aluminium and plastic.

The highly combustible cladding was used on the building because it was cheap and because of the “incompetence of the organisations and individuals involved in the refurbishment” – including architects, engineers and contractors – all of whom thought safety was someone else’s responsibility, the report said.

The government and authorities failed over decades to assess the dangers of such cladding, Moore-Bick said.

The tenant management organisation of the local authority is accused of manipulating the process of appointing the architect who oversaw the installation of the cladding.

The report reserved particular criticism for the companies that manufactured the cladding, accusing them of engaging in “systematic dishonesty,” manipulating safety tests and misrepresenting the results to claim the material was safe.

‘Gut-wrenching’

The London Fire Brigade was also criticised for a “chronic lack of effective management and leadership”.

The report said firefighters were not adequately trained to deal with a high-rise fire and were issued with old communications equipment that did not work properly.

The report made multiple recommendations, including the introduction of tougher fire safety rules, the establishment of a national fire and rescue college and a single independent regulator for the construction industry to replace the current mishmash of bodies.

London Mayor Sadiq Khan said the report was a “gut-wrenching” read. He said that “more must now be done to hold those responsible to account, including banning any of the companies held responsible by the inquiry from receiving any public contracts as the police and CPS look into bringing criminal prosecutions”.

‘Web of blame’

The lapses and mistakes detailed in the report could trigger criminal charges. Nineteen organisations and 58 individuals are currently under investigation.

Charges could include corporate manslaughter, gross negligence manslaughter, fraud, health and safety offences and misconduct in a public office.

However, police have said charges will not be filed before 2026.

Survivors and bereaved families expressed concern that the report may spread blame too widely to see anyone punished properly.

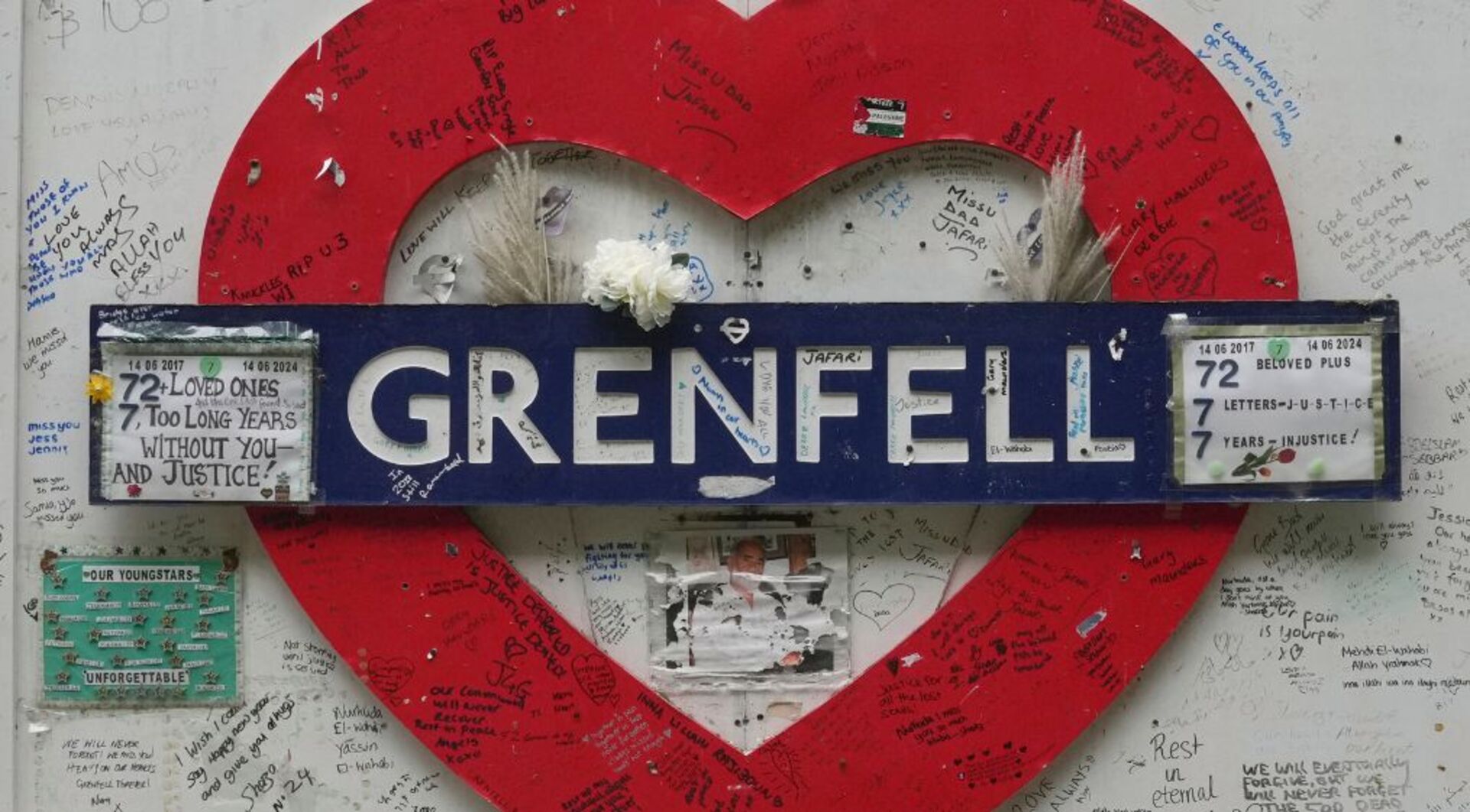

“We were denied justice for seven years and now told there will be several more years,” the Grenfell Next of Kin group said in a statement on Wednesday. “Our realistic concern is that the ‘web of blame’ presented through the inquiry will be a barrier to our justice.”

Relatives of victims blamed the inquiry for delays, saying they were not consulted on whether it should be set up.

“None of the direct kin families were informed about an inquiry,” said Hisam Choucair, a member of the group, who lost six family members in the blaze.

The inquiry, he said, had been ordered the morning after the fire when survivors were “looking for our families in hospitals and in shock”.

“Our voices were robbed. We were not given the choice, and we did not know the consequences and the impact on our right to justice.”

‘Seeds of disaster’

The disaster has left many people living in buildings covered in similar cladding, fearful of a repeat tragedy.

Moore-Bick said warning signs emerged as early as 1991 that some kinds of materials, in particular ACM panels with unmodified polyethylene cores, were “dangerous”.

However, the authorities had failed to amend statutory guidance on the construction of external walls.

“That is where the seeds of the disaster were sown,” he says.

In the wake of the fire, the UK government banned metal composite cladding panels for all new buildings and ordered similar combustible cladding to be removed from hundreds of tower blocks across the country.

But due to the expense, work is yet to be carried out on some apartment buildings because of wrangling over who should pay.

A fire in Dagenham, East London, just over a week ago illustrated the continuing risks.

More than 80 people had to be evacuated in the middle of the night after waking to smoke and flames in a block where work to remove “non-compliant” cladding was partially completed.

According to UK government data up to July, 4,630 buildings standing at 11 metres or higher still have unsafe cladding, with work on replacing the material yet to start on half of them.

Shattered

All those who died in the building had been “overcome by toxic gases produced by the fire,” said Moore-Bick. The fire was above all a “human tragedy”, he added, referring to lives lost, families torn asunder, homes destroyed and a community shattered.

The victims came from 23 countries and included taxi drivers and architects, a poet, an acclaimed young artist, retirees and 18 children.

It prompted soul-searching about inequality in Britain. Located in one of London’s richest neighbourhoods, Grenfell was a public housing building and many of its inhabitants were working-class people with immigrant roots.