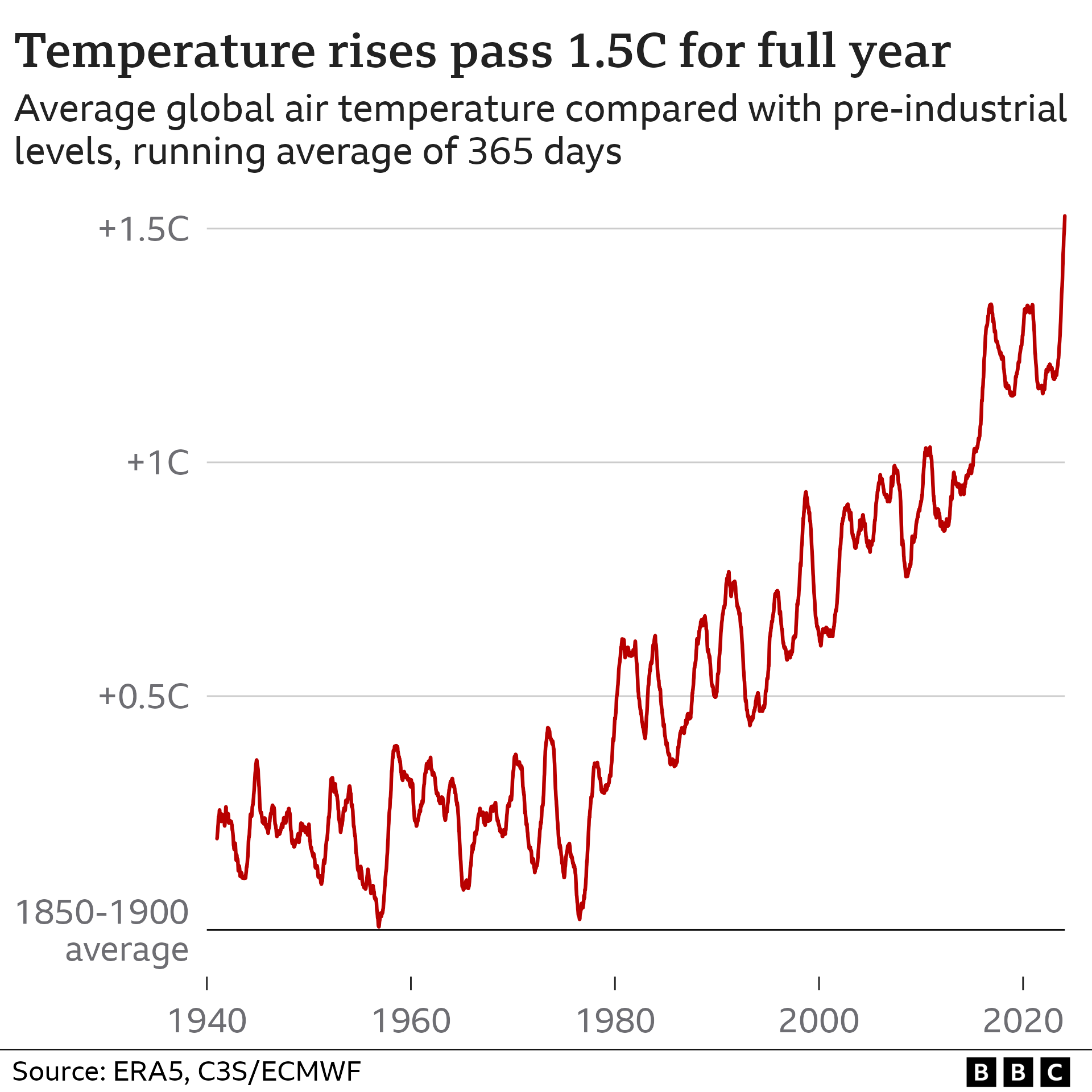

For the first time, global warming has exceeded 1.5C across an entire year, according to the EU’s climate service.

World leaders promised in 2015 to try to limit the long-term temperature rise to 1.5C, which is seen as crucial to help avoid the most damaging impacts.

This first year-long breach doesn’t break that landmark Paris agreement, but it does bring the world closer to doing so in the long-term.

Urgent action to cut carbon emissions can still slow warming, scientists say.

“This far exceeds anything that is acceptable,” Prof Sir Bob Watson, a former chair of the UN’s climate body, told the BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme.

“Look what’s happened this year with only 1.5C – we’ve seen floods, we’ve seen droughts, we’ve seen heatwaves and wildfires all over the world.”

The period from February 2023 to January 2024 reached 1.52C of warming, according to the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. The following graph shows how that compares with previous years.

The latest climate warning comes amid news that the Labour Party is ditching its policy of spending £28bn a year on its green investment plan in a major U-turn. The Conservatives also pushed back on some key targets in September.

This means the UK’s two main parties have scaled back the type of pledges that many climate scientists say are needed globally if the worst impacts of warming are to be avoided.

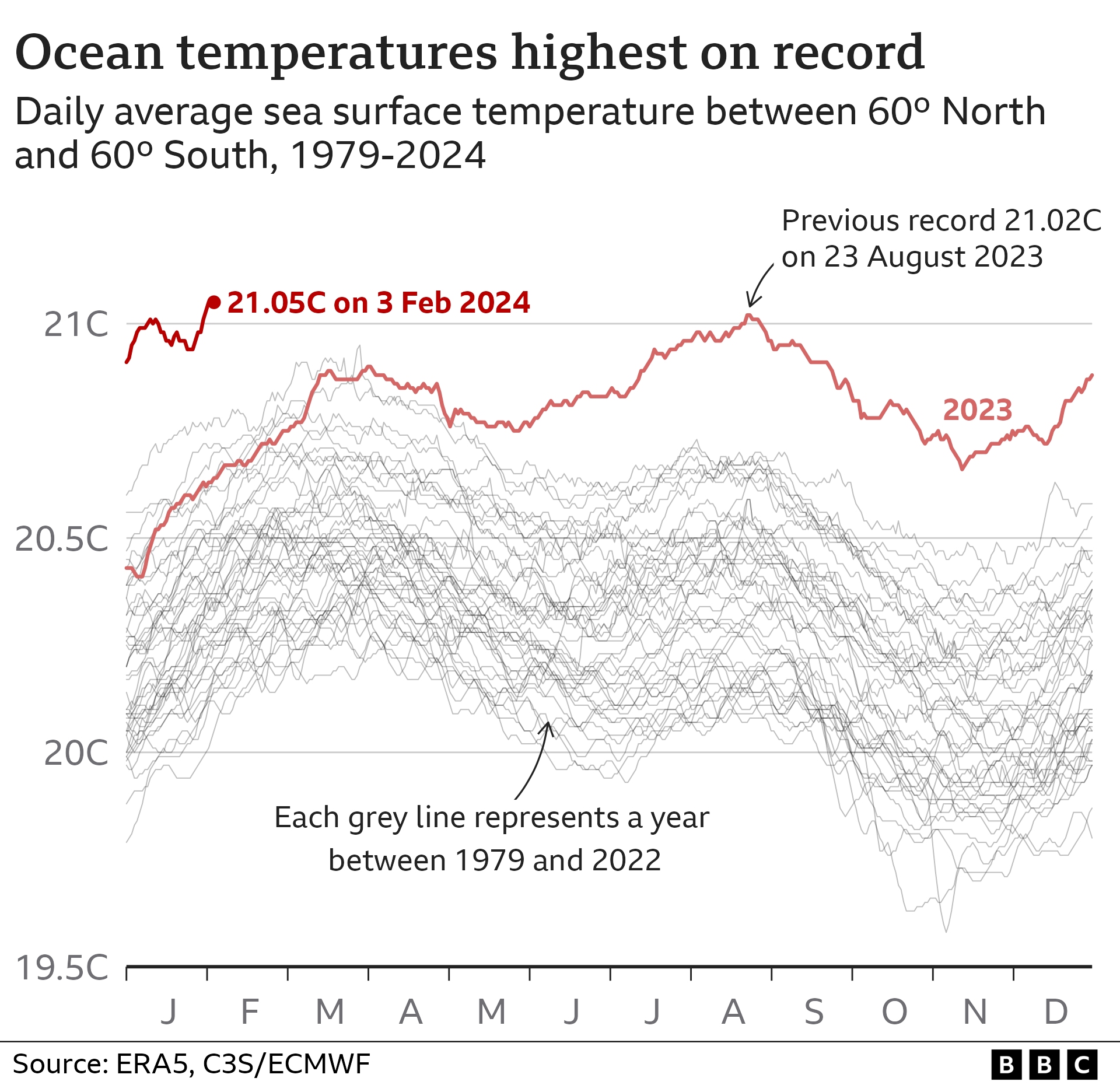

The world’s sea surface is also at its highest ever recorded average temperature – yet another sign of the widespread nature of climate records. As the chart below shows, it’s particularly notable given that ocean temperatures don’t normally peak for another month or so.

Science groups differ slightly on precisely how much temperatures have increased, but all agree that the world is in by far its warmest period since modern records began – and likely for much longer.

Limiting long-term warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels – before humans started burning large amounts of fossil fuels – has become a key symbol of international efforts to tackle climate change.

A landmark UN report in 2018 said that the risks from climate change – such as intense heatwaves, rising sea-levels and loss of wildlife – were much higher at 2C of warming than at 1.5C.

Why has 1.5C been broken over the past year?

The long-term warming trend is unquestionably being driven by human activities – mainly from burning fossil fuels, which releases planet-warming gases like carbon dioxide. This is also responsible for the vast majority of the warmth over the past year.

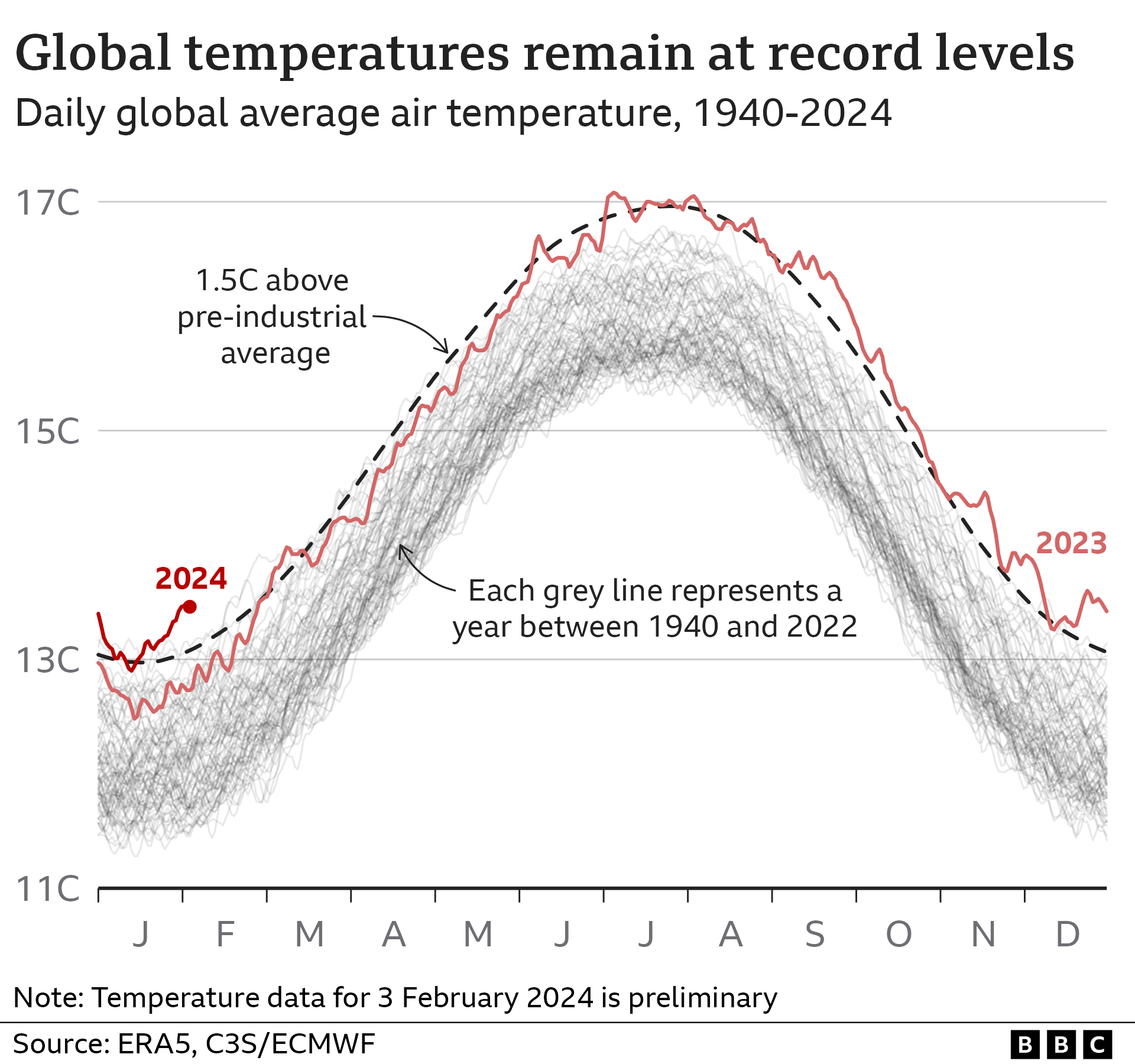

In recent months, a natural climate-warming phenomenon known as El Niño has also given air temperatures an extra boost, although it would typically only do so by about 0.2C.

Global average air temperatures began exceeding 1.5C of warming on an almost daily basis in the second half of 2023, when El Niño began kicking in, and this has continued into 2024. This is shown where the red line is above the dashed line in the graph below.

An end to El Niño conditions is expected in a few months, which could allow global temperatures to temporarily stabilise, and then fall slightly, probably back below the 1.5C threshold.

But while human activities keep adding to the levels of warming gases in the atmosphere, temperatures will ultimately continue rising in the decades ahead.

Can we still limit global warming?

At the current rate of emissions, the Paris goal of limiting warming to 1.5C as a long-term average – rather than a single year – could be crossed within the next decade.

This would be a hugely symbolic milestone, but researchers say it wouldn’t mark a cliff edge beyond which climate change will spin out of control.

The impacts of climate change would continue to accelerate, however with every little increase in warming – something that the extreme heatwaves, droughts, wildfires and floods over the past 12 months have given us a taste of.

An extra half a degree – the difference between 1.5C and 2C of global warming – also greatly increases the risks of passing so-called tipping points.

These are thresholds within the climate system which, if crossed, could lead to rapid and potentially irreversible changes.

For example, if the Greenland and West Antarctic Ice Sheets passed a tipping point, their potentially runaway collapse could cause catastrophic rises to global sea-levels over the centuries that followed.

But researchers are keen to emphasise that humans can still make a difference to the world’s warming trajectory.

The world has made some progress, with green technologies like renewables and electric vehicles booming in many parts of the world.

This has meant some of the very worst case scenarios of 4C warming or more this century – thought possible a decade ago – are now considered much less likely, based on current policies and pledges.

And perhaps most encouragingly of all, it’s still thought that the world will more or less stop warming once net zero carbon emissions are reached. Effectively halving emissions this decade is seen as particularly crucial.

“That means we can ultimately control how much warming the world experiences, based on our choices as a society, and as a planet,” says Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at US group Berkeley Earth.

“Doom is not inevitable.”